The Old Man’s chiseled jaw and unmistakable stern brow emerged from the craggy cliffside as if by magic. Amidst the visual chaos of the mountainside, his stone face offered a moment of unexpected clarity. The first written mention of the Old Man of the Mountain was in 1805, though no one truly knows how long this natural wonder graced the top of Cannon Mountain in Franconia Notch, New Hampshire.

When viewed from the north at certain angles, a series of protruding ledges on Cannon Mountain combined to create the Old Man’s profile. Viewed from anywhere else, the Old Man’s face would vanish – morphing back into the granite from which he came.

At 40 feet tall and 25 feet wide, the “face” was made up of five granite ledges that had been shaped by freeze and thaw cycles. As water seeped between the rocks and froze, the expanding ice created cracks and fissures in the granite, gradually sculpting the Old Man’s profile.

Twenty-two years ago, gravity and erosion brought this icon back down to earth, yet his legacy remains intact to this day. The Old Man’s distinctive profile is emblazoned on everything from newspapers and gift shop memorabilia to state highway signs and license plates. He is even featured on New Hampshire’s state quarter.

Decades after his geological demise, why do we continue to so fervently honor his legacy?

An enduring Symbol: Why we continue to honor the Old Man of the Mountain

For some, his rugged countenance was – and still is – emblematic of New Hampshire’s terrain and weather-proof residents. He captured the essence of the Granite State’s motto: “Live Free or Die.”

For others, the reverence for the Old Man is pure nostalgia. I, for one, still remember my father crouching down to match my three-year old stature, leading my eyes with an outstretched hand as he pointed up at the cliff in the distance. The Old Man of the Mountain was able to capture a feeling. Like a mirror, he reflected the inspiration and affection I felt when I first laid my eyes on that rugged White Mountain landscape.

The White Mountains is where I experienced the unfiltered natural world for the first time. Ragged peaks, towering cliffs, fragrant pines and unspoiled views tugged at my childhood soul. It was a feeling best described by John Muir: “The mountains are calling and I must go.”

I think we remain infatuated by the Old Man because he was a tangible anthropomorphized representation of our own connection to the natural world.

When we stroll through the woods, it’s the shapes in the bark of passing trees that stop us and make us shout, “Hey – look! The trees have eyes!” As we wander along a trail, it’s the soft rustle of leaves overhead that makes us pause and whisper, “Listen… the forest is speaking.”

It’s easier for us to relate -to and appreciate aspects of the natural world that have human-like characteristics and qualities. The Old Man’s features allowed us to create a powerful human connection with something entirely nonhuman. In a sense, this close-but-not-quite human entity shortened the distance between us and our environment, connecting us together as descendents of the same mother nature.

In a sense, this close-but-not-quite human entity shortened the distance between us and our environment, connecting us together as descendents of the same mother nature.

His countenance mirrors our own – the look on our face when we reach a 4,000-foot New Hampshire summit or the awe that floods over us as we look across layer upon layer of blue mountain magic.

In a fascinating study published by the Journal of Environmental Psychology, researchers found that the anthropomorphic term “Mother Nature” strengthens our mental imagery by fusing a women-nature association, affecting our environmental outlook and behavior. According to research by Waytz et al. (2010), individuals who perceive nature as a human being are more inclined to respect it and apply the same social norms of fairness to the natural world as they would in interactions with other people. Anthropomorphism can unify humans and nature within a shared moral framework, encouraging us to extend the same consideration and ethical responsibility to nature as we would to another human being.

Across time, different peoples have shared a common relationship with the Old Man of the Mountain.

Born of stone: The origins of the Old Man of the Mountain

To the Abenaki – the indigenous people of the northeastern woodlands – the Old Man of the Mountain was known as the “Stone Face.” According to Abenaki legend, a great leader called Nis Kizos became part of the mountain after waiting for the return of his beloved Tarlo. For months, Kizos waited for her, keeping a well-fed fire ablaze to guide his love back to him. Atop Cannon mountain, the leader-turned-to-stone would continue looking for his love.

White settlers “discovered” the Old Man’s existence and his presence was first documented in written records in 1805 by road surveyors Francis Whitcomb and Luke Brooks.

The granite profile garnered nationwide attention in 1850 when Daniel Webster, a New Hampshire native, famously wrote:

“Men hand out their signs indicative of their respective trades; shoemakers hang out a gigantic shoe; jewelers a monster watch; and the dentist hangs out a gold tooth; but up in the Mountains of New Hampshire, God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there He makes men.”

“If the spectator approached too near, he lost the outline of the gigantic visage, and could discern only a heap of ponderous and gigantic rocks ... Retracing his steps, however, the wondrous features would again be seen; and the farther he withdrew from them, the more like a human face, with all its original divinity intact, did they appear."

These descriptions of the beauty of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and of the enigmatic stone face overlooking them, helped establish the region as one of America’s earliest tourist destinations. The advent of rail travel in the 1850s made the region much more accessible from cities such as Boston and New York, leading to a surge in visitors. With guidebooks in hand, many of these visitors were coming to see the Old Man of the Mountain.

The area became so popular that numerous inns and hotels were built in Franconia Notch to accommodate the growing numbers of tourists arriving to see the Old Man and other nearby natural wonders like the Flume Gorge. The aptly named Profile House – the largest of these early hotels – opened in 1853 and provided guests with trail access to explore Cannon Mountain – where the Old Man resided – and nearby Echo and Profile Lakes.

Fighting the Inevitable with a Face-Lift

While local tourism was strengthening, the Old Man was aging. In the early twentieth century, it became evident that the seemingly-eternal Old Man was slowly crumbling away. Restoration efforts began in 1916, when the nearby Profile House hotel hired the Old Man’s first care-taker. Rods and turnbuckles were installed on the profile to secure fissures in his granite forehead.

In 1957, the New Hampshire legislature allocated $25,000 to repair the Old Man, and in 1958, four more turnbuckles were installed and a water diversion ditch created to divert water away from the Old Man’s head.

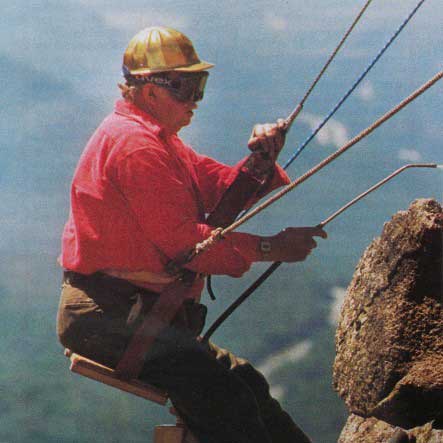

Beginning in 1960, Niels Nielsen, began his 30-year-shift as the Old Man’s caretaker. Niels, a bridge superintendent for the State of New Hampshire, would dangle over the Old Man’s brow in a bosun’s chair to pull weeds and strain test the turnbuckles.

Mourning a Geological Death

On May 3, 2003, the Old Man collapsed.

Braving the wind and the rain on that spring morning, locals gathered at the base of Cannon Mountain to look up at what once was.

A heavy downpour and ponderous clouds helped create a funeral-like atmosphere. While many of those in attendance wore colorful rain jackets, it was a solemn affair. Huddled beneath umbrellas and scattered around covered picnic tables, people gathered to say goodbye to the Old Man.

Some locals said that it felt as though they’d lost a family member. Some left flowers.

Throughout the day, questions about possible “reconstruction” floated through the mountain air. But how would someone go about reconstructing something that was not created by human hands to begin with?

Still, it didn’t take long for the Granite State to assemble the Old Man Restoration Task Force. It wasn’t a superhero squad gearing storm the mountains, but rather a sincere attempt to piece the Old Man back together. Created by Gov. Craig Benson, the task force was charged with finding an appropriate way to memorialize the Old Man.

State officials received hundreds of proposals. Some entrepreneurs and engineers testified in favor of rebuilding the granite icon. In a letter to New Hampshire officials, James Schoefer, vice president of marketing and sales for Createk – a plastics company that specializes in fake rocks – pitched the idea of recreating the Old Man out of plastic.

Others believed the Old Man was right where he belonged. If nature brought him into the world, it should have the last word when taking him out of it. After months of testimony, the Task Force made its decision.

It decided against any attempt to rebuild or restore the rock formation. Instead, the Task Force recommended constructing a tribute that would recreate the iconic view as seen from the visitor’s perspective at the memorial.

The Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund grew out of the Task Force and took on the responsibility of creating a permanent memorial to the Old Man. In 2011, the Legacy Fund raised $250,000 to construct “Profile Plaza.”

The centerpiece of Profile Plaza is a series of steel “profilers” designed to recreate the Old Man’s visage when looked at in alignment with the surrounding cliff. These artistic installations allow visitors to visualize the formation as it once appeared.

The plaza also features interpretive panels that share the geological history, cultural significance, and preservation efforts surrounding the Old Man. Benches and walking paths make it a peaceful place to reflect, while the nearby Echo Lake and Pemigewasset River enhance the natural charm of the area.

Reflections: Lessons from an Old Man

The Old Man of the Mountain has crumbled. In many ways, our natural world is crumbling, too. But his lingering spirit still speaks to us – encouraging us to connect, appreciate and protect.

As the climate continues to shift in New England, we will likely lose other iconic features of our natural landscape as well. Warmer autumn nights, and invasive plants and insects put the region’s trees under stress – stifling its iconic fall foliage.

Come winter, warmer temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns are already impacting New England’s rich skiing tradition. In recent years, reduced snowpack has threatened the region’s wintertime recreation and undermined the local economies that depend on winter tourism.

Much of New England may even become too warm for sugar maples, effectively shifting their habitat northward. Can you imagine Vermont or New Hampshire without tapered glass bottles filled with golden syrup?

Now more than ever, we need to find ways to connect to the natural world around us. Whether it be a park in your town or the National Forest a few hours away, I encourage you to connect with these places as you would connect with a friend. Search for those “tree eyes” looking back at you. Greet the critters that scurry below you, join the chorus of birds that sing above you.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer eloquently put it, “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.” I encourage you to befriend the forest – to rest your face on her bed of moss or hug her craggy bark. And, of course, scour her cliffs for hidden stone faces.

To look out across a landscape and have the burning desire to protect it – that’s the outlook we must embrace. In order for us to mobilize – as people did as they mourned the loss of the Old Man – we need to find ways to connect with place. Only then can we find in ourselves the firm commitment to defend it.