When you think “New England,” what images come to mind? Is it the sight of a lobster shack, shrouded by mist along the coast of Maine? Maybe it’s the cobblestone streets of Boston or the quaint, postcard-perfect towns of Vermont. Whatever comes to mind, I bet it isn’t stone.

But when it comes to understanding the region that so many of us call home, few symbols speak as loudly (or perhaps, as quietly) as New England’s stone walls. Scattered throughout its forests, rambling across its hillsides, and lining its rutted country roads, the ever-present stone wall is an iconic feature of New England’s storied landscape. They remind us of a time when New England wasn’t covered by lush forest, but instead shaved bald by a patchwork of farms as far as the eye could see.

Today, the variety of flora found within the region’s forests is a defining and beloved feature of New England’s landscape. Atop the peaks in the White Mountains, gnarled stands of blue-green spruce trees stand resolutely against some of the fiercest winds on the planet — their growth stunted by unforgiving weather and their branches whipped into shape by the wind. Across Massachusetts and Connecticut, sugar maples, stirred by cold autumn nights, boast a fiery spirit.

But it was not always this way.

These forests are deceptively unspoiled. Deep within their breadth, it is easy for us to assume that we tread upon virgin soil. The solitude that can be found within these seemingly primeval woodlands makes us feel as if we’ve stepped beyond the threshold of civilization and into the wild. Stone walls, however, remind us that this land was formerly exercised, and far from wild.

Over the course of 200 years between the late seventeenth and the late nineteenth century, New England lost its forests. By some estimates, nearly eighty percent of the region’s forests were erased by the mid-nineteenth century.

This rampant deforestation came at the hand of determinedly self-sufficient Yankee farmers. The once wild frontier forests were clear-cut to create pastures, crop enclosures and hayfields as far as the eye could see. In place of old-growth forest, a vast network of walls defined the landscape — farm walls used to outline crop fields and manage livestock.

Upon deforesting the region, farmers were confronted with a new foe: stones. Copious amounts of rocks – left behind by the region’s glacial past, which up until then had largely remained trapped beneath the forest’s network of roots – now littered crop fields and grazing land.

In a herculean effort by generations of New England farmers, two-handed stones were lifted from crop fields and brought to the edge of farm enclosures — some tossed into crudely stacked piles, others deliberately laid into walls.

Since then, the stone walls that snake across the region have been overtaken by forest: enveloped by roots, bearded by lichen and encrusted with moss. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the vast majority of New England’s sustenance farms were abandoned – wood constructions succumbed to gravity and cleared fields were reclaimed by forest.

The crisscrossing stone walls that remain intact from this bygone era beautifully capture the dramatic transformation of New England’s landscape since the arrival of European settlers. They symbolize the immense change brought to the region alongside the introduction of European agricultural practices. But most of all, they serve as a lasting reminder of our destructive relationship with the natural world and the heavy footprint we’ve left on it.

New England's glacial past

If you’ve ever hiked in the region, you know just how rocky New England can be (New Hampshire, after all, is referred to as ‘the granite state’). You can thank the region’s glacial past for those sore knees, twisted ankles and New England’s ever-present stone walls.

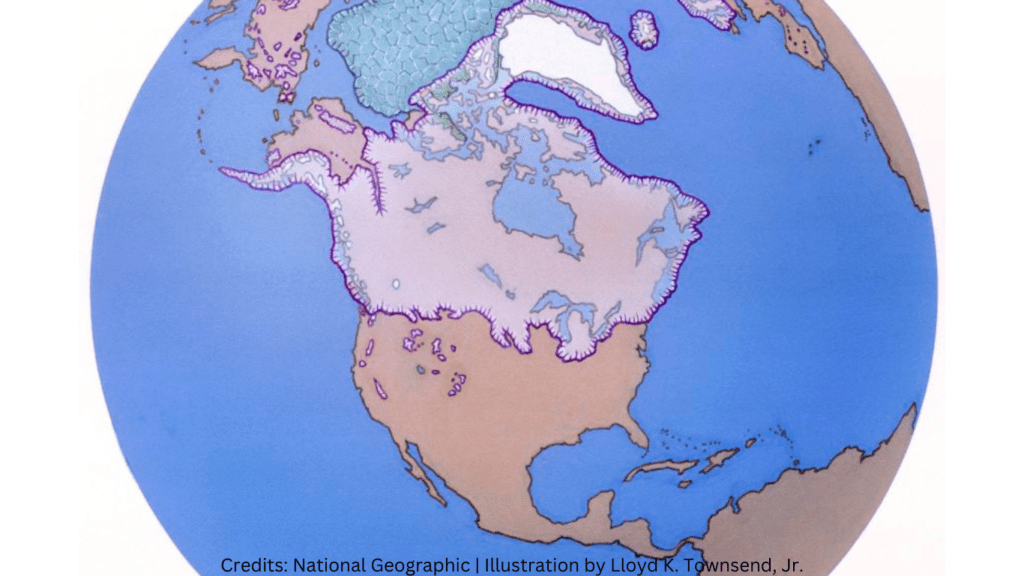

Measuring four thousand miles in diameter and two miles thick at its center, the Laurentide Ice Sheet was the principal glacier covering North America during the last Ice Age (about 2,600,000 to 11,700 years ago). The Laurentide Ice Sheet was most massive some 18,000 years ago, when it extended outward from central Canada to cover all of New England.

Periodically expanding and retracting, this monstrously large ice sheet stripped the land clean, down to the bedrock, as it plowed across New England. As it slowly melted and retreated to the North, the ice sheet left behind an abundance of rock that had been pulled up and carried across the landscape. It left behind scattered glacial rocks and a barren landscape of bedrock.

Only hard and igneous rocks like granite, or metamorphic rock that were subject to high pressure like gneiss, are capable of surviving the crushing forces of glacial movements. Softer rock was pulverized or crushed into sand.

Thousands of years later, the heavy rocks that were left behind – referred to as glacial till and lodgement till – were yanked out of the ground and laid by farmers to construct New England’s stone walls.

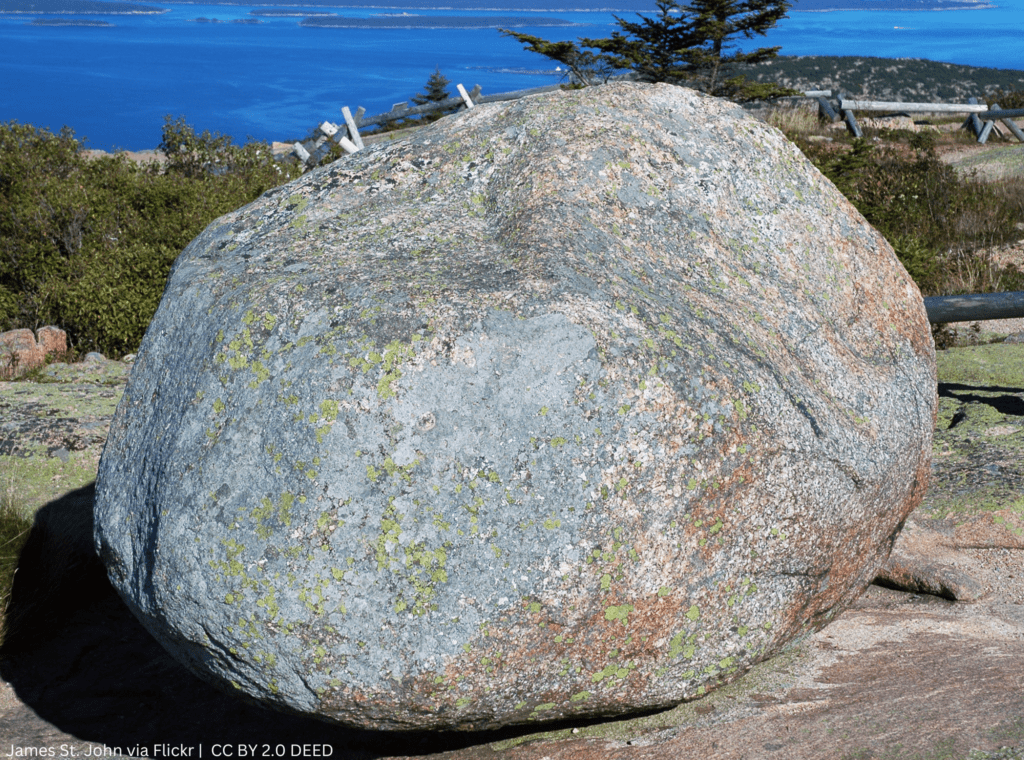

As Robert Thorson explains in Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls, “[lodgement] till was created when countless blocks of slate, schist, granite, and gneiss were plucked from ledges by moving ice, then forced downward to the bedrock under grinding, wet conditions.” (Thorson, 46). The largest of these glacial artifacts, called glacial erratics, can be the size of buildings and have become landmark boulders in many areas across New England.

Over the course of thousands of years following the retreat of Laurentide’s glaciers, the bitterly cold and lifeless landscape of strewn rock transformed into tundra characterized by sparsely populated ground-hugging plants. An abrupt period of warming around 11,500 years ago began turning the tundra into isolated patches of coniferous forests. Networks of roots and flora proliferated atop once-naked terrain.

This new ground cover allowed rich, organic soils to stabilize rather than erode after every rainfall. Slowly but surely, forests emerged on top of the glacial till – burying glacial rock until European settlers came along.

Newcomers: The arrival of European settlers

The agricultural practices brought by English settlers – namely husbandry – would fundamentally change New England’s landscape.

Settlers were determined to transplant their Old World system of mixed husbandry, based on raising crops and livestock, into the New World. Fencing and enclosures, physical barriers to protect crops from animals, are critical to this system of mixed husbandry. By spreading their system of land enclosure across the region, these settlers would forever change the land.

Over time, English settlement moved inland from the coast. The first generations of settlers kept to the coast in community-oriented Puritan settlements. As the colonial era wore on, later generations of Puritans began pushing back against the strictly regulated lifestyle demanded by their religious communities. They sought distance from their religious settlements along the coast by moving westward into the forested interior – like restless teenagers eager to move away from home.

Robert Thorson perfectly captures this movement in his book Stone by Stone:

Third- and fourth- generation Puritans, especially the young and restless, answered this call with their feet, moving inland from the coast and upward from tidal rivers toward the uninhabited interior where land was readily available. These sons and daughters launched the first great emigration from the ancestral colonies… Individualism… was on the rise. (Thorson, 83)

This shift away from community-oriented living toward a more self-reliant, subsistence lifestyle set the stage for an explosion of smallholding farms across New England.

Self-reliant farmers began settling the interior and cleared the forest to create treeless crop enclosures and open land for livestock. For the New England farmer, the conservation of timber was hardly a concern: survival was paramount. Wood was required to construct fences to keep livestock out of crop fields and to build and heat homes.

Driven by a growing demand for wool, farmers continued to clear forest at an astonishing rate to create pasture for a booming population of sheep. While clearing the forest, New England farmers spared only a small number of large trees on the periphery of their property to provide shade for their livestock. Follow an old stone wall through the woods for long enough, chances are you’ll likely come across one of these spared shade-providers.

As a result of intensive farming practices, there was a substantial loss of topsoil and networks of forest roots were stripped from the land. Trees help retain water and topsoil; without trees, soil begins to erode and wash away. Glacial tillage that had remained trapped beneath this once dense net of organic material began to creep its way to the surface.

Frost heaves and soil erosion contributed to the seemingly endless spawn of stones that kept appearing on Yankee soils. Frost heaving is an uplifting process that is responsible for raising stones up through the soil. Absent a network of trees and roots, deeper subsoil becomes more exposed to the cold, causing a deeper freeze of groundwater. As a result, the soil becomes more affected by cycles of freezing and thawing – cycles that shift underlying stone and bring stones upward to the surface of the soil.

Fields completely cleared in the fall would be littered with a new batch of stones in the spring. “Yankee farmers called them New England potatoes because they appeared like magical crops in fields that had been picked clean the year before,” says Robert Thorson, author of the book Stone by Stone. Others believed that the arrival of new stones was the work of the devil. In reality, it was their own doing.

Building New England's stone walls

To those who undertook the backbreaking work of creating them, stone walls were largely considered to be an ugly by-product of land cultivation. Stones impeded productive cultivation on the farm, so farmers hauled stones to the edges of their enclosures.

Until widespread timber shortages became a reality as a result of deforestation, fences to enclose farmland were built using a combination of wood and stone. As wood became scarce, farmers increasingly turned to the endless amount of field stones to construct new barriers. As Susan Allport explains in her book Sermons in Stone, “Had the colonists not been so profligate with wood, these walls might never have been built.”

Stone walls were laid without mortar using a one-on-two, two-on-one building technique. This layering technique prevented gaps in one tier from coinciding with gaps in the tier above it. The size of stones laid into the wall were based on what a farmer could carry using both his hands and were stacked into walls that rarely exceeded chest height. The function of these walls remained simple: barriers to define different types of land use on a farm (i.e. hayfields from cornfields) and to prevent livestock from entering cultivated fields.

"Sheep Fever" and the Golden Age of stone walls

The height of New England’s agricultural economy came in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. The growth of industry coupled with tariffs imposed on the import of English goods during the War of 1812 spelled success for the Yankee farmer.

“Sheep fever” – referring to the exploding demand for wool and the subsequent sheep-raising boom that followed – swept New England. Farmers began growing their flocks to meet the heightened demand for wool, which also precipitated the expansion of stone walls to manage increased livestock.

At the heart of this craze was the Merino sheep. Renowned for its ample, non-scratchy wool, the merino sheep – brought over to the United States from Spain – fueled the growing demand for wool. The following excerpt from an article titled “History of the Merino Sheep Mania” published by The Calendar in 1856 deftly captures the merino sheep craze:

It was said that their fleeces were of the first texture, and that the introduction of the breed into this country would enable our woollen manufactories, then in their infancy, to produce broad-cloths that would compete successfully with the finest European fabrics. Our farmers became excited… These sheep were exactly what was required to enrich both our agriculturists and our manufacturers. The mania spread itself rapidly.

Sheep fever empowered New England’s farmers, while simultaneously accelerating the region’s deforestation. By 1840, seventy-five percent of New Hampshire was open land. The New England of the mid-nineteenth century would have been unrecognizable to us. But like all booms, “sheep fever” would not last.

Farm Abandonment

Beginning in the mid-1800s, farming declined precipitously across New England. For one, the United States was quickly shifting from an agricultural society to an industrial one. Not only were young men leaving their family farms across New England in search of opportunities in burgeoning cities, but larger-scale commercial farms with new farming technology located closer to cities were better suited to fulfill urban demand.

What’s more, the lure of the American West was intoxicating. Parcels of good land became available through the Homestead Act of 1862 and legendary tales of untamed frontiers, gold-rushes and eden-like country west of the Rockies was enough to convince many Yankees to venture west.

The allure of stone-free prairie land in the midwest also pulled many farmers away from the stony soils of New England. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and expanded railroad networks also contributed to the decline of New England’s agricultural economy. Increased connectedness between the east coast and Midwest via railroad and waterway allowed production from the rich agricultural soil of the Midwest to compete locally with products in the northeast. Self-sufficient farmers could simply not compete.

As New England’s farming economy waned, nature inevitably returned. Absent man’s unending attempt to maintain order, saplings sprouted in former crop fields and farmhouses drooped in their foundations. As Robert Thorson artfully put it, “As the trees came back, the walls came apart. Disorder was reclaiming order… land was reverted to its pre-pioneering condition.”

Looking Back

They may be easily overlooked, but stone walls tell the story of New England’s dramatic environmental transformation that began with the arrival of European settlers. They serve as enduring symbols of man’s ability to completely reshape the natural world, but they also remind us of nature’s inevitability: She will reclaim all that humanity has borrowed from her.

Since the abandonment of many farms in New England, reforestation has ensued. The secondary forests that blanket the region today – full of beech, hemlock, oak and maple – feel like old-growth to us.

The decline of small-scale farms coupled with the rise of industrialism undoubtedly contributed to the reforestation of New England, but so too did the rise of conservationism. No longer deeply constrained by the pressures of survival and scarcity, today we look at New England’s natural landscape very differently: Not as a commodity, but as a home that must be protected and conserved.

We will never experience the primeval forests that early European settlers witnessed centuries ago. But if we continue to conserve forests and protect our mature trees, future generations will.